Plotting complex variable functions

- Plotting the function’s module

- Plotting the real and imaginary part

- Domain coloring

- Conformal mapping

- Plotting as a vector field

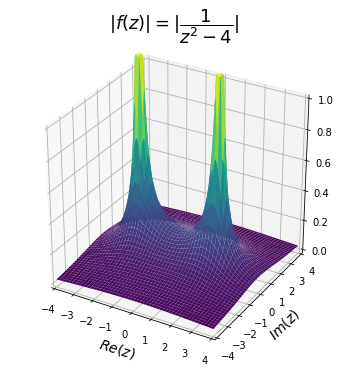

Plotting the function’s module

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

N = 500

lim = 4

x, y = np.meshgrid(np.linspace(-lim,lim,N),

np.linspace(-lim,lim,N))

z = x + 1j*y

f = abs(1/(z**2-4))

f[f>1.3] = 1.3 # Cut the function at the poles for decoration purposes.

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6,6))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection="3d", xlim=(-lim,lim), ylim=(-lim,lim), zlim=(0,1))

ax.plot_surface(x, y, f, cmap="viridis", shade=True, alpha=1)

ax.set_xlabel("$Re(z)$", size=14)

ax.set_ylabel("$Im(z)$", size=14)

ax.set_title("$|f(z)|=|\dfrac{1}{z^2-4}|$", size=18, pad=30)

plt.show()

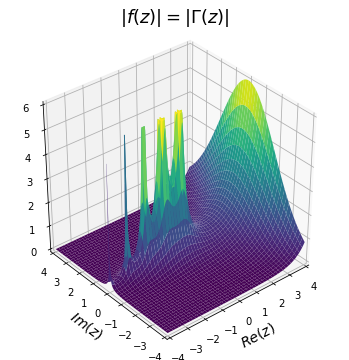

from scipy.special import gamma

f = abs(gamma(z))

f[f>6] = 6

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6,6))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection="3d", xlim=(-lim,lim), ylim=(-lim,lim), zlim=(0,6))

ax.plot_surface(x, y, f, cmap="viridis", shade=True, alpha=1)

ax.set_xlabel("$Re(z)$", size=14)

ax.set_ylabel("$Im(z)$", size=14)

ax.set_title("$|f(z)|=|\Gamma (z)|$", size=18, pad=30)

ax.view_init(azim=-130, elev=35)

plt.show()

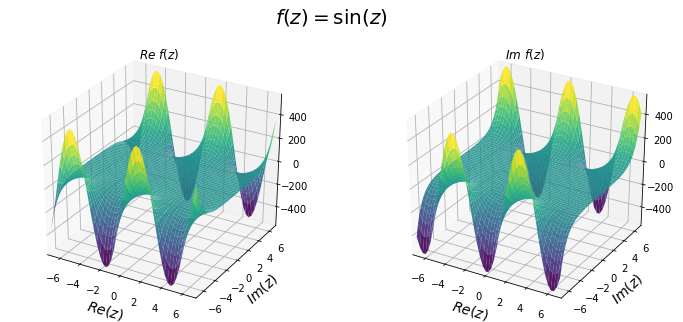

Plotting the real and imaginary part

N = 50

lim = 7

x, y = np.meshgrid(np.linspace(-lim,lim,N),

np.linspace(-lim,lim,N))

z = x + 1j*y

f = np.sin(z)

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(12,5))

fig.suptitle("$f(z) = \sin(z)$", fontsize=20)

ax1 = fig.add_subplot(121, projection="3d", xlim=(-lim,lim), ylim=(-lim,lim))

ax2 = fig.add_subplot(122, projection="3d", xlim=(-lim,lim), ylim=(-lim,lim))

ax1.plot_surface(x, y, f.real, cmap="viridis", shade=True, alpha=0.9, label="Re f(z)")

ax2.plot_surface(x, y, f.imag, cmap="viridis", shade=True, alpha=0.9, label="Im f(z)")

ax1.set_zlim(f.real.min(), f.real.max())

ax1.set_xlabel("$Re(z)$", fontsize=14)

ax1.set_ylabel("$Im(z)$", fontsize=14)

ax1.set_title("$Re \,\, f(z)$") # \, adds space

ax2.set_zlim(f.imag.min(), f.imag.max())

ax2.set_xlabel("$Re(z)$", fontsize=14)

ax2.set_ylabel("$Im(z)$", fontsize=14)

ax2.set_title("$Im \,\, f(z)$")

plt.show()

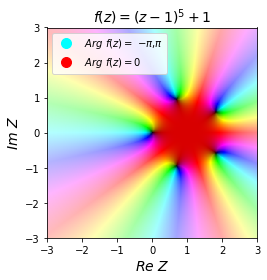

Domain coloring

from colorsys import hls_to_rgb

def colorize(fz):

"""

The original colorize function can be found at:

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/17044052/mathplotlib-imshow-complex-2d-array

by the user nadapez.

"""

r = np.log2(1. + np.abs(fz))

h = np.angle(fz)/(2*np.pi)

l = 1 - 0.45**(np.log(1+r))

s = 1

c = np.vectorize(hls_to_rgb)(h,l,s) # --> tuple

c = np.array(c) # --> array of (3,n,m) shape, but need (m,n,3)

c = np.rot90(c.transpose(2,1,0), 1) # Change shape to (m,n,3) and rotate 90 degrees

return c

N = 500

lim = 3

x, y = np.meshgrid(np.linspace(-lim,lim,N),

np.linspace(-lim,lim,N))

z = x + 1j*y

f = (z-1)**5+1

from matplotlib.lines import Line2D

legend_elements = [Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', color='cyan', label='$Arg$ $f(z) =$ $-\pi$,$\pi$', markersize=10, lw=0),

Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', color='red', label='$Arg$ $f(z)=0$', markersize=10, lw=0)]

# Create the figure

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.legend(handles=legend_elements, loc='upper left')

img = colorize(f)

ax.imshow(img, extent=[-lim,lim, -lim,lim])

ax.set_xlabel("$Re$ $Z$", fontsize=14)

ax.set_ylabel("$Im$ $Z$", fontsize=14)

ax.set_title(r"$f(z)=(z-1)^5+1$", fontsize=14)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

lim = 2

x, y = np.meshgrid(np.linspace(-lim,lim,N),

np.linspace(-lim,lim,N))

z = x + 1j*y

f = 1/((z-1)*(z+1)**2)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(5,5))

ax.legend(handles=legend_elements, loc='upper left')

img = colorize(f)

ax.imshow(img, extent=[-lim,lim, -lim,lim])

ax.set_xlabel("$Re$ $Z$", fontsize=14)

ax.set_ylabel("$Im$ $Z$", fontsize=14)

ax.set_title(r"$f(z)=\frac{1}{(z-1)(z+1)^2}$", fontsize=14)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

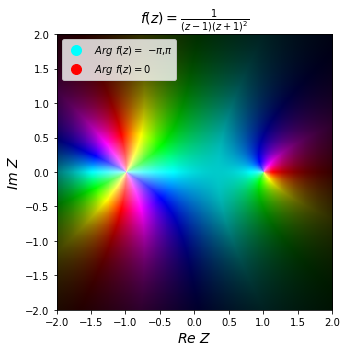

#__exp(1/z)___________________________________________

lim = 1

x, y = np.meshgrid(np.linspace(-lim,lim,N),

np.linspace(-lim,lim,N))

z = x + 1j*y

f = np.exp(1/z)

fig, (ax, ax2) = plt.subplots(1,2,figsize=(10,4))

ax.legend(handles=legend_elements, loc='upper left')

img = colorize(f)

ax.imshow(img, extent=[-lim,lim, -lim,lim])

ax.set_xlabel("$Re$ $Z$", fontsize=14)

ax.set_ylabel("$Im$ $Z$", fontsize=14)

ax.set_title(r"$f(z)=e^{1/z}$", fontsize=14)

#__sin(z)/z___________________________________________

lim = 10

x, y = np.meshgrid(np.linspace(-lim,lim,N),

np.linspace(-lim,lim,N))

z = x + 1j*y

f = np.sin(z)/z

ax2.legend(handles=legend_elements, loc='upper left')

img = colorize(f)

ax2.imshow(img, extent=[-lim,lim, -lim,lim])

ax2.set_xlabel("$Re$ $Z$", fontsize=14)

ax2.set_ylabel("$Im$ $Z$", fontsize=14)

ax2.set_title(r"$f(z)=\frac{\sin(z)}{z}$", fontsize=14)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

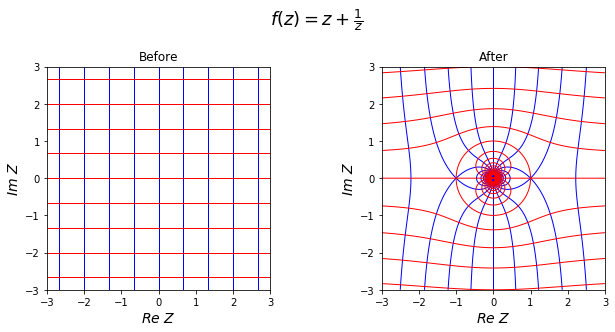

Conformal mapping

\(f(z) = \mbox{Re} f(z) + i \, \mbox{Im} f(z)\)

\[\begin{align} \mbox{Re} f(z) & = C_1 \\ \mbox{Im} f(z) & = C_2 \end{align}\]def f(z):

return z + 1/z

# The x and y coordinates

lim = 3

N = 300

Xv = np.linspace(-lim, lim, N)

Yv = np.linspace(-lim, lim, N)

X, Y = np.meshgrid(Xv, Yv)

# Values of f as a function of z=x+iy

Z = X+1j*Y

Fv = f(Z)

lv = np.linspace(-10,10,31)

# Contours of constant Re f(z) and Im f(z) as a function of x and y

fig, (ax, ax2) = plt.subplots(1,2,figsize=(10,5))

fig.suptitle(r"$f(z)=z+\frac{1}{z}$", fontsize=18)

ax.set_aspect("equal")

ax2.set_aspect("equal")

ax.contour(Xv, Yv, X, colors='blue', linestyles='solid', levels=lv, linewidths=1)

ax.contour(Xv, Yv, Y, colors='red', linestyles='solid', levels=lv, linewidths=1)

ax.set_xlabel("$Re$ $Z$", fontsize=14)

ax.set_ylabel("$Im$ $Z$", fontsize=14)

ax.set_title("Before")

ax2.contour(Xv, Yv, np.real(Fv), colors='blue', linestyles='solid', levels=lv, linewidths=1)

ax2.contour(Xv, Yv, np.imag(Fv), colors='red', linestyles='solid', levels=lv, linewidths=1)

ax2.set_xlabel("$Re$ $Z$", fontsize=14)

ax2.set_ylabel("$Im$ $Z$", fontsize=14)

ax2.set_title("After")

plt.subplots_adjust(wspace=0.5)

plt.show()

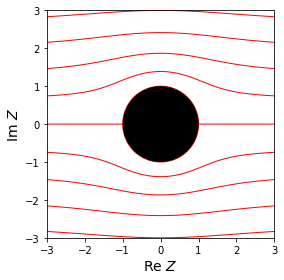

from matplotlib.patches import Circle

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.set_aspect("equal")

Circ = Circle((0,0), radius=1, facecolor="black", alpha=1, zorder=10)

ax.add_patch(Circ)

ax.contour(Xv, Yv, np.imag(Fv), colors='red', linestyles='solid', levels=lv, linewidths=1)

ax.set_xlabel("Re $Z$", fontsize=14)

ax.set_ylabel("Im $Z$", fontsize=14)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

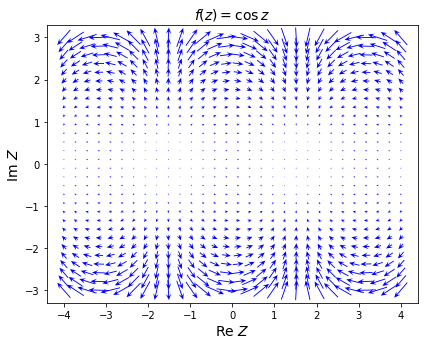

Plotting as a vector field

def f(z):

return np.cos(z)

# The x and y coordinates

lim = 3

N = 30

Xv = np.linspace(-lim-1, lim+1, N)

Yv = np.linspace(-lim, lim, N)

X, Y = np.meshgrid(Xv, Yv)

# Values of f as a function of z=x+iy

Z = X+1j*Y

Fv = f(Z)

lv = np.linspace(-10,10,31)

# Plotting part

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6,5))

ax.set_aspect("equal")

ax.set_xlabel("Re $Z$", fontsize=14)

ax.set_ylabel("Im $Z$", fontsize=14)

ax.set_title(r"$f(z)=\cos \, z$", fontsize=14)

ax.quiver(X, Y, np.real(Fv), np.imag(Fv), color='blue', pivot="middle", norm=True, headwidth=6, headlength=7 )

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

References

-

C. Fernández González (n.d.). ¿Cómo representar funciones en variable compleja? [online]. Portal.uned.es. Available at: http://portal.uned.es/pls/portal/docs/PAGE/UNED_MAIN/LAUNIVERSIDAD/

UBICACIONES/01/DOCENTE/CARLOS_FERNANDEZ_GONZALEZ/

VARIABLE%20COMPLEJA%20GEOGEBRA/REPRESENTARVC.PDF -

C. Maggi, et al. (n.d.). Aplicaciones gráficas de funciones complejas. [online] academia.edu. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/2211067/Aplicaciones_gr%C3%A1ficas_de_funciones_complejas

-

G. Viswanathan (2014). Domain coloring for visualizing complex functions. [online] Gandhi Viswanathan’s Blog. Available at: https://gandhiviswanathan.wordpress.com/2014/10/07/domain-coloring-for-visualizing-complex-functions/

-

En.wikipedia.org. (2019). Domain coloring. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domain_coloring

-

Wikidot.com. (n.d.). The Casorati-Weierstrass theorem. [online] Available at: http://mathonline.wikidot.com/the-casorati-weierstrass-theorem

-

N. Hall. (2018). Conformal mapping, Joukowsky transformation. [online] grc.nasa.gov. Available at: https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/k-12/airplane/map.html

-

S. Ganguli. (2008). Conformal Mapping and its Applications. [online] Iiserpune.ac.in. Available at: http://www.iiserpune.ac.in/~p.subramanian/conformal_mapping1.pdf